Amsterdam by Bite

Neighbourhoods | Housing | Parks

Tourism Weather | Money | Cards & Pictures | Travel | Bike | Excursions | Hotels | Postcard

Going out Movies | Dancing | Theatre

Culture Art | Artists | Musea | Design

Music Classic | Jazz | Musicians | Podia | Lyrics

Reading Writing | Language | Authors

Lifestyle Gay | Bisexual | Sexuality | Love

Education & Science General | Elementary Schools | High Schools | Vocational Training | Higher Education | Universities

Socio-Politics Politics | Environment

Religion Bahá'í | Buddhism | Catholic | Humanism | Islam | Jewish | Protestant | Quakers | New Age

Introduction

In this study a new way of analyzing class societies will be proposed. You don’t have to be an expert on this subject to know that the social sciences are crowded with rivalizing class theories for many years now. It’s even hard to identify a common ground on which the different approaches compete with each other. A secondary objective of this study is a systematic review of all approaches on class analysis.

I started this project with the idea that it would be possible to reconstruct a coherent and empirically sustainable class theory out of all the contributions that have been made. I undertook a long search for the assumptions, basic concepts, methodology and internal structure of class theories, and I evaluated the results of empirical and historical studies on class relations. Getting more precise ideas about the present ‘state of the art’, I understood that there is no developed class theory with a refined and systematic conceptual apparatus which can be applied in empirical and historical studies. What we do have are some useful partial class theories, a lot of concepts which are not well related to each other, and some theories or theoretical perspectives that can only claim to be ‘general’ by drastically reducing their object.

In the meantime I’ve worked together with Veit Bader on a project called proto theory of social inequalities and collective action. In this project we elaborated a general frame of reference which will be used here to construct a new general approach for the analysis of class relations. The primary objective of this study is to develop the cornerstones for a transformational model of class analysis.

Of all the restrictions of this book I will only mention three. First, it is not a detailed reconstruction of a particular class theory or of a specific research tradition on class analysis. Cursorily I deal with the history of the class concept, but I don’t present an extensive historical survey on the development of different class theories. So it isn’t a historical or chronological review of different approaches, theoretical perspectives or authors. The analytical currents and authors will be dealt with in a problem oriented fashion, i.e. they will be analyzed on those points where they are relevant for the construction of the transformational explanatory model. Along these lines we will get more precise ideas about the pros (analytical power and strong points) and cons (internal obstacles, aporia, theoretical blocks and lacunae) of the research traditions on class. For that matter the transformational class model can serve as an analytical and methodological framework for critical reconstructions of specific class theories.

Second, it is ‘only’ an attempt at theory construction. It provides an outset for a systematic class theory. Basic concepts are delimitated and related to each other, several analytical levels are differentiated and compared and once in a while cautious statements about causal explanations will be made. So it isn’t a ‘system of class theory’, though the chapters can be read as essays in systematic class theory.

Third, this study doesn’t contain a new empirical analysis of class structures in modern capitalism. The transformational class model merely claims to be a better alternative as a frame of reference for empirical studies than other approaches. Empirical and historical studies will be used whenever they are relevant for the construction of the heuristic model (particularly in those parts where I illustrate actual trends in the development of class structures). Otherwise I restrict myself to the formulation of research questions and strategies and some remarks on operationalization problems. The book is divided into four parts.

Part 1 Introductory skirmishes

I. Class analysis as a scientific problem

The social structure of our society, in which the capitalist mode of labour dominates, reveals itself to us as a gigantic stack of social inequalities. Class inequality is one of its elementary forms. There are very few aspects of social live which are not touched by class differences. The class position of an individual affects not only the economic live —the labour, income and consumption relations— but also the lifestyle, social consciousness, culture, politics, and even the ultimate and intimate things like life expectancy, sexual relations, marriage, religion, chances on hapiness and mental healtn. Class positions do not only have a strong influence on power positions in all kind of organizations, but also structure the sociale interaction chances — the selection of friends and lovers, neighbours and acquaintances. And last but not least: class positions do not only generate inequalities of sociale live chances, but also strongly determine chances of political action. The class dimensions of all those aspects of our economic, social, cultural and political existence has been demonstrated over and over by many social scientist. Class inequalities are a fundamental structural form of social inequality. They are generated by the inequal control on social resources which allow some —exploiting— classes to appropriate the surplus labour of other —exploited— social classes.

«Class» is an essentially contested concept which is fraught with unpleasing associations. Some sociologists have said that class is a ‘largely obsolete’ [Nisbet 1959] or ‘increasingly oudmoded concept’ [Clark/Lipset 1991]. In short: ‘Class is passé’ [Pakulski/Waters 1996:1]. In the capitalist metropoles the idea of class has become a kind of forbidden thought. When people use the term class they have a fair chance that this will be interpreted as the symptom of a perverted mind and a jaundiced spirit. However, there has been and probably will always be others who think that it’s impossible to be silent on class and class struggle as long as the societal structures and social relations of capitalist societies are structured by exploiting mechanisms. As long as this is the case, the problem of class and class conflict will remain a crucial theme of scientific and politicial debate. In these debates almost every word has an explosive and controversial meaning. The word class has soaked up so much meaning that is has become bulky to use. Debates about class often become conversations in which people talk past each other because they are talking about different dimensions of class. Anyone who has the temerity to write about class theory is immediately plunged into controversy by the very way he or she approaches the subject.

In the first chapter class analysis is described as a scientific problem. It gives empirical indications about the ways class relations influence our daily live,consciousness and attitudes. Do people still experience that they actually live in a class society? And if so, how do they articulate these experiences and what are the consequences for their cultural attitudes and political actions? After a short survey on the origins of the class vocabulary a first attempt is made to construct an elementary typology of class definitions in the social sciences.

Figure 2 First Typology of Class Definitions

The diversity of theoretical perspectives on class will be outlined, and the themes about which they compete will be identified. To pave the way for further investigation I give a preliminary delimitation of the knowledge object of class theory and of the structural and historical scope of class analysis.

The general knowledge object of class theory are the social relations between and in the social classes and their mutual struggle. So class analysis relates both to the class structuration of social positions in specific societal formations as to the ways in which class-based collective actors are generated. More specific it relates to:

- the historical conditions of the origin of exploitation and class relations.

- the basis and forms of existence of social groups from their place in a specific system of social organization of labour.

- the structural-positional and historical-dynamic relations between and in the social classes and class factions.

- the power relations between classes, class factions and social strata within classes.

- the conditions and forms of the formation of classes into historical relevant political actors in the process of class struggle (i.e. class-based social movements).

- the process of transformation or elimination of antagonistic social class relations.

Class theory a regional theory of certain aspects of the social structures in antagonistic formation that are characterized by exploitation relations. But also tends to be a general theory in the sense that the class structuration of all social relations belongs to its object. Although class theory should not be reduced to a disciplinary theory (it is not an ‘economic theory’), it not a super theory which embraces all forms of social inequality (it is not a general ‘theory of social inequality’).

Class analysis includes theory construction and empirical-historical research on structure and dynamics of class relations. The scope of class analysis can be outlined by three elements.

- Theoretical analysis of structure and dynamic of class relations on the abstraction level of a ‘pure’ mode of labour: differential positions of the classes and class factions in the structure of the reproduction process and the global transformations in these relations.

- Empirical research of concrete-historical class relations in a specific country, in a deliminated period of time. The general analysis of the structure and development of the classes is connected with historical and national peculiarities of certain countries or regions (like place in international, national and regional relations, specific formation of the national and local state, the effects of conflict traditions and cultural heritage).

- The analysis of the forms of consciousness and organization of social classes in the process of political class formation and of the actual power positions in class conflicts. This includes not only the analysis of politically organized forms of class action, but also —and perhaps even in the first place— of the elementary, molecular or everyday forms of class-based social action, and of the lifestyles and cultures that accompany these forms of social action.

Class analysis is a very broad research program. It is theory guided research of the empirical-historical contradictions between classes and class factions which can serve as a bases for the evaluation or design of political strategies of exploited, dominated working classes against exploiting, dominant classes (including the intermediate or derived classes and social strata which are connected with these fundamental or main classes). It will be clear the political and normative orientations do play an important role in this scientific program.

II. Class analysis as a political problem

In this chapter class analysis will be treated as a political problem. It contains a critical discussion of the rather ambitious political claims which are normally attached to class analysis, especially in the Marxist tradition. It has often been said that scientific research on class relations should make it possible to make judgements on:

- The perspective of a classless society

Class analysis is oriented at the clarification of the perspective of a classless society. It has implications in terms of what is at stake in a transformation of society into a socialist/communist direction. - The revolutionary subject

A comprehensive research on the power relations between the social classes would make it possible to identify the transformational actors of class relations. It should identify and characterize the potential and actual powers that are able to transform the capitalist society in a socialist direction. - The political action strategy of the labour movement

Class analysis would make it possible to clarify alternative types of socialist class politics. This is important for the strategic discussion on the ways revolutionary and radical emancipation movements can break through the the barriers of bourgeois class states and realize a democratic-libertarian form of socialism/communism.

In all three respects class analysis has become a political problem, not in the least in socialist circles. The discussion of these claims informs the formulation of my own normative and political assumptions. This is the normative principle that directs this study: «all individuals should have equal liberties for optimal development and use of their individual differentiated human potentials and capacities, in such a way that no privileges can arise.»

III. Analytical Problem Structuration

This chapter presents a structure for the analysis of the highly aggregated problems a class analysis has to tackle. I tried to design a fine-grained analytical network which can be used in theoretical and empirical research programmes. The basic idea is simple: for a systematic analysis of complex class relations we need a clear view of the levels of abstraction and problem axes. In this chapter I use this ‘problem structuration’ for a systematic review of the actual supply of class theories. Class concepts are differentiated on the basis of four systematic questions.

- First, are classes primarily defined in terms of a specific type of collective action or in terms of social structures (or structural positions in specific social relations)? With this question we differentiate between structure and action-oriented approaches, and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of these approaches.

- When classes are defined in structural terms, there is a second question: on which level of social integration are analysed? With this question we differentiate between societal, organizational and interactional approaches, and will discuss the strengths and weaknesses of these approaches.

- When classes are defined in terms of a specific level of social integration, I pose the third question: on which level of structuration of collective action are they defined? Classes can be defined on the level of objective positions, of mobility processes, of class habitus & class specific lifestyles, of types & levels of consciousness, or in terms of specific conditions for political class action and class consciousness.

- When classes are defined in terms of objective positions, I pose the fourth and final question: which levels of structuration of objective class positions are differentiated? Classes can be defined in terms of production and/or distribution relations, of labour and/or market relations. The evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of both production and market based class conceptions will provide some crucial elements for the construction of a transformational class analysis.

Figure 4 Second Typology of class definitons

I compare and evaluate all existing class theories which vary (i) in levels of abstraction, (ii) in units of historical and empirical analysis, (iii) in actional or structural frames of reference, (iv) in levels of social integration (v) in levels of structuration of class action, (vi) in levels of structuration of objective class positions. With this method I will demonstrate, not only which theoretical, methodological and empirical choices have been made by different class analysts, but also which choices can be made, and what the choices are that I prefer or decline.

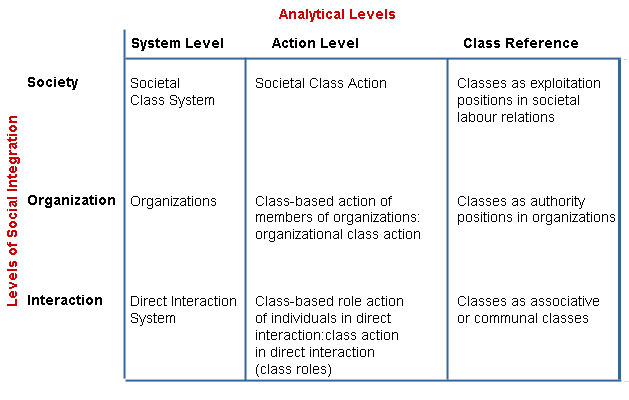

Class inequalities and structures can be analyzed on several levels of social integration. I claim that there are three levels of social integration which have to be clearly demarcated: the societal level, the organizational level and the interactional level. Actions and communications in interaction systems occur in direct, physical copresence of the actors. The actions and communications in organizations can to some extent break away from these direct interactions through the development of organizational positions and structures. The societal level is always the most comprehensive social system of all social actions and action systems which are connected to each other in a communicative and actual way. These most comprehensive social systems can be ‘societies’ in the strict sense (such as the bourgeois society) or societal subsystems (such as the capitalist economic system).

The crucial question is on which level of social integration the class concept should be defined. Some authors define the class concept exclusively or mainly on the societal level. They define classes in terms of structural positions in some kind of societal relations which can not be reduced to inequal interaction or organizational chances and which can neither be explained departing from them. Classes have been defined as structural positions in societal labour relations (in the marxist tradition), in societal distribution or market relations (in the neo-weberian tradition) or in societal professional relations (professional classes in the functionalist tradition).

Other authors define classes exclusively or mainly in terms of unequal positions in organisations and of the social live and political power chances which derive from such organizational positions. In the tradition of the elite theory (Pareto, Msca, Michels, Burnham, Dahrendorf) classes have been defined in terms of inequalities in authority positions. Ralf Dahrendorf has given the most influential modern phrasing for this approach:

- “By social class shall be understood such organized or unorganized collectivities of individuals as share manifest or latent interests arising from and related to the authority structure of inperatively coordinated associations. It follows from the definitions of latent and manifest interests that social classes are always conflict groups” [Dahrendorf 1959:238].

In the organizational approach classes are interpreted as conflict groups which are determined by their position in authority or power relations of organizations. The implicit or explicit assumption thereby is that the significance of formal organizations in all social relations is growing and that therefore also the relative structuring force of organizational power is growing.

In the interactional approach classes are exclusively or mainly defined in terms of inequalities in interaction systems which result from dominating role structures (i.e. networks of class-specific social relations). The class concept is concentrated on or reduced to specific sociale interaction systems (like living together, sharing a house) and to the chances which result from these direct personal relations (‘face-to-face relations’). Conceptualizations and empirical research are concentrated on the degree of homogeniety/heterogeniety of personal contacts (circles of friends and acquaintences), marriage ties, neighbourhood relations, intervisiting and clique relations etc. In this approach a class is interpreted as a direct interaction group: ‘associative class’, ‘community class’. The most influential and explicit phrasing of an interactional class concept can be found in the work of the cultural anthropologist W. Lloyd Warner. He defines class as:

- “the largest group of people whose member have intimate acces to one another. A class is composed of families and social cliques. The interrelationship between these families and cliques in such informal activities as visiting, dances, reception, teas, and larger informal affairs, constitute the structure of social class” [Warner 1945:772-3].

Joseph Schumpeter [1927] can be seen as the trendsetter of this tradition, which next to the community studies of Warner c.s especially has been stimulated by the symbolic interactionist (Goffman, Bulmer, Bott, Laumann, Kimberley, Sennet/Cobb, Vanneman) and the exchange theoretical tradition (Homans, Balu, Ekeh, Berger/Zelditch, Anderson). Recently many of these approaches flow together in network analysis.

Figure 6 Societal, Organizational and Interactional Class Definitons

I contend that class relations are structured on all levels of social integration: societal, organizational and interactional. And therefore class relations ought to be analyzed on each of these levels. There are however no class theories with such a scope that they encompass all three integration levels and in which these levels are analytically clearly separated. Most theories concentrate only on one integration level. Non-reductionist class theories should in this respect fulfil at least two requirements. First, they should not only be able to make a clear analytical differentiation between the levels of social integration, but also specify the interrelatedness between these levels. Second, they should make clear whether the class concept can be defined exclusively or primarily on one level of social integration, and if so, why? These problems will be dealt with in chapter V.

IV. Social Inequality and Classes

In general most scientists agree that class relations are a specific structural form of social inequality. This chapter therefore starts with a brief analysis of concept and forms of social inequalities: natural and social inequalities, social differentiation and social inequality, positional and allocative inequalities, social inequality as structured inequality. From this point of view six general proposition are presented. Together they form the ‘hard core’ of a research program of class analysis.

- Classes are an aspect of the social structure of a society, therefore they have to be defined in relational and not in gradual terms.

- Classes are structurally defined in terms of positions in societal labour relations which are characterized by an institutionalized and structural appropriation of surplus labour.

- Class relations are fundamentally antagonistic because classes can only be defined in terms of a specific relation (positive or negative) to the appropriation of surplus labour. The basic classes of all class societies are the exploited classes of producers of surplus labour and exploiting classes who are able to appropriate and accumulate surplus labour.

- Class relations are a specific form of asymmetrical power relations. Exploitation is a specific type of asymmetrical power. Therefore classes should be analyzed in terms of extractive power and domination relations, and not in terms of professions or aspects of technical/functional divisions of labour.

- Class relations are dynamic relations. They change continuously in the process of struggle between exploiting classes who try to contain or expand their extractive powers and exploited classes who are using their developmental powers to limit or eliminate their exploitation.

- Classes are embedded in specific historical forms of exploitative labour relations. Therefore classes are historical phenomena which change their character when the mechanisms and forms of exploitation are modified.

These propositions constitute a platform on which the rest of this book is built, and they will be specified, elaborated upon and concretized in the next chapters. Every chapter opens with an additional thesis, which will be delineated in relation to other approaches and then substantiated and expanded.

Part 2 Structuration of Objective Class Positions

V. Outline of a Transformational Class Analysis

This chapter outlines the frame of reference of the transformational class approach. It presents a heuristic model to break out of the misleading dichotomy between structuralist and actionist class approaches.

- Structuralist approaches concentrate exclusively on the analysis of the basic structures of class relations and do not - other than by association - allow systematic, substantiated connections with the political class action of social actors: they analyze ‘structures without actors’.

- Actionist approaches on the other hand, concentrate fully on political actions of class actors, but they neglect to analyse the social structuration of these actions: they analyze ‘unstructured actors’.

A transformational class approach starts from a position beyond this controversy between structure and action-oriented approaches. The transformational model is based on the following thesis: class action is structured by class relations and class structures are generated, reproduced and transformed by class action. The object of a transformational approach is neither ‘class structure’ nor ‘class action’, but class specific structuration of action. So the central theme will be the analysis of the ‘structuration of class action’.

My heuristic model emphasizes the multiple character of this structuration of class action. I contend that there are at least five levels on which class action is structured. Class action is primarily structured by the inequalities and differences of (i) objective class positions and of (ii) social classes and class communities. It is also structured by inequalities and differences of (iii) specific habitus and lifestyles, and by (iv) types of action motivation and degrees of class awareness and class consciousness. Finally, class action is structured by (v) a series of specific conditions for the development of class consciousness and political class action, like specific forms of law and state.

I also contend that we need an heuristic model which can distinguish the levels on which class action is integrated. I have built upon a distinction between societal, organizational and interactional levels of integration. The transformational class model is constructed along the combined lines of these levels of structuration and integration.

VI. Labour Relations and Modes of Labour

The central thesis of this chapter is that class relations are primarily anchored in exploitative labour relations on the societal level. To substantiate this claim the basic concepts of ‘labour’, ‘labour relations’ and ‘mode of labour’ (and not ‘mode of production’) will be defined. ‘Mode of labor’ will be defined as a specific combination of

- a specific distribution of control over three types of direct resourses: material conditions, objects and means of labor; individual qualifications; forms of co-operation, combination and leadership.

- a specific dominant goal of labor: aimed as use value, exchange value, maximum exchange value, or capital accumulation; and

- a specific type of social dominance and subordination relations within and in relation to labor organizations.

With these conceptual tools I concentrate on two of the most controversial modes of labour: the domestic and the ‘petty commodity’ mode of labour. The explanation of these modes of labour contributes to the solution of some of the most tricky puzzles in class analysis.

We’ll get a pretty good idea why conceptions that define class in terms of labor or production processes (both in marxist as in non-marxist approaches) or in terms of occupations (in occupational sociology tradition) do not work. But we also get a clear sight on the weaknesses of synthetical conceptions in which the concept is stretched to the extreme of a broad mode of production (Poulantzas) or of the system of social inequalities in general (Bourdieu).

VII. Labour Relations and Market Relations: Credential Exploitation

The central thesis of this chapter is that classes are structurally defined in terms of positions in both labour relations and distribution relations. This thesis implies a demarcation from ‘productivist’ class concepts (which concentrate exclusively on labour or production relations) and from ‘distributive’ class concepts (which focus on distribution or market relations).

To substantiate this thesis the key conception of exploitation is explained. I have tried to elaborate a general concept of exploitation which holds independently from Marxist labour theory of value. This general concept gets some flesh and bones with the specification of the various mechanisms and (direct and indirect) forms of exploitation. These specifications serve as a prelude to the construction of a theoretically sustained and empirically informed typology of exploitation positions, which must not be identified with class positions.

I have tried to show the usefulness of this approach in a detailed analysis of a form of exploitation which has, up to now, been relatively underexposed: credential exploitation. The primary target was to get a sharp conception of credential exploitation. In a brief discussion on the principal differences between qualification and credentials I first specify the basis of credential exploitation. Then the mechanism of credential exploitation is explored as well as the possibilities to reproduce this form of exploitation (how to accumulate ‘credential rents’?). Finally, I designate the conditions under which credential exploitation can constitute distinct and durable class positions. This conception of credential exploitation is used to analyze the intermediate class positions of professionals and experts in advanced capitalism. I have shown the possibilities (and problems!) of this concept of credential exploitation for an empirical analysis of these class categories. Particularly in this chapter, the work of Erik Olin Wright is discussed: a critical tribute to a man which has produced so many stimulating contributions to modern class analysis.

VIII. Classes and Domination Relations: Organizational Exploitation

The central thesis of this chapter is that the analysis of exploitative class relations cannot be confined to the societal level. Class relations must be analysed on the organizational level as well. The reason is that under certain conditions exploitative class relations are generated on the organizational level of integration. Superior positions within the formal structures of labour organizations are not as such class positions. Under certain conditions however these ‘elite positions’ allow their incumbents to exploit their subordinates to a non-trivial degree and on a durable basis. Whenever this is the case, these superior organizational positions can and should be treated as class positions. To tackle this phenomenon, I elaborate on the different types of asymmetrical power relations, and especially, on the connection between relations of exploitation and domination.

Figure 10 Fundamental types of positional inequality

The centre piece of this chapter is the analysis of another controversial form of exploitation: organizational exploitation. The same approach as in the previous chapter is followed. First, a general exploration of the basis, the mechanism and the chances of reproduction of organizational exploitation (how to accumulate ‘loyalty rents’?); next an analysis of the conditions under which organizational exploitation can lead to genuine class positions. The general concept of organizational exploitation is used in an illustrative analysis of the intermediate class positions of managers in capitalism.

IX. Classes and Interactional Relations: Clientele Exploitation

The central thesis of this chapter is that under certain conditions exclusive positions in networks of interaction can constitute structural positions of exploitation, and can therefore be treated as potential class positions. Building upon anthropological and sociological network theories two types of exclusive positions in interactional or interpersonal networks are analyzed: selective associations and patronage. Patronage is a specific kind of network of social relations between individuals or groups who control substantial unequal resources: the ‘clients’ are more or less forced to render ‘personal services’ and to pay a ‘patronage rent’ (protection premium) to get access to resources which are vital for them, and the patron or boss who controls these resources and will give his clients ‘personal favours’ in return.

This is the point of reference for a discussion of the clientele form of exploitation. A now familiar approach will be followed: first an exploration of the bases, mechanisms and reproduction chances of the clientele form of exploitation, next an exploration of the possibilities of the development of distinct exploitation and class positions. In the last part of this chapter I explore another form of exploitation which can occur in all societies in which discriminating prestige relations are institutionalized. This form of ‘ascriptive exploitation’ is illustrated by the operation of ‘sexploitation’, that is exploitation of woman by man on the basis of a dominant positive social prestige of man.

X. Exploitation Positions, Class Positions, and Class Structure

The central thesis of this chapter is that we have to make a clear distinction between exploitation positions (structural positions in exploitative relations) and class positions (structural positions in class relations). The failure to make this distinction is one of the greatest weaknesses of all modern class theories. Class positions are always embedded in exploitative relations, but not all positions in exploitative relations will generate distinct and stable class positions. The concept of «class position» is further developed in five steps. I istinguish (i) main and intermediate class positions; (ii) durable and temporary class positions; (iii) primary and derived class positions; (iv) singular and multiple class positions; (v) direct and mediated class positions. To illustrate some of these distinctions I analyse the class position of the independent or traditional middle classes.

Part 3 Structuration of class action: from Class Position to Political Actors

The processes which are responsible for the origin and development of organized political actors and class actions are analyzed in several steps, following the sequence of levels of structuration of my heuristic model.

XI. From Class Positions to Social Classes

The genesis of social classes (‘potential action collectives’) is analyzed starting from the structural chances for people to change class positions (‘obstructed mobility chances’). The central thesis is that the durability of the connection of individuals to a class position is crucial for the genesis of social classes and for elementary forms of social organization (‘the social fabric’) which are expressed in networks of class specific interpersonal relations (‘class communities)’. After an elaboration of the significance of class communities, some synthetic conclusions are drawn about structuration levels of objective class situations. The remaining part of this chapter is devoted to the problematic relation between classes, class factions and social strata.

XII. Class specific forms of Habitus and Lifestyles

This chapter concentrates on the mediating function that habitus fulfils between objective class positions and the social consciousness and political actions of individuals. The central thesis is that class structure and class based forms of social organization are the ground on which relatively coherent, class specific forms of habitus and lifestyles and life expectations may arise, which in their turn have a strong impact on class identities and political class actions. With critical reference to the work of Pierre Bourdieu the concept of «class habitus» will be specified.

Five dimensions of habitus are spelled out and illustrated: the somatic, psychic, esthetic, normative and linguistic forms of habitus. A more extensive analysis is made of the general and class specific properties of the physical habitus (‘body language’).

The elaborations on habitus make up the context for a short exploration of the social and cultural «lifestyles» and of class specific or class related «cultures».

XIII. Types of Orientation and Class Consciousness

The central thesis of this chapter is that collective actors on a class basis can emerge only when the members of a social class develop their own class specific habitus, lifestyles and cultures, as well as a class identity, a class awareness or consciousness. I analyze different types of orientation and motivation which are relevant for the structuration of class consciousness and class action.

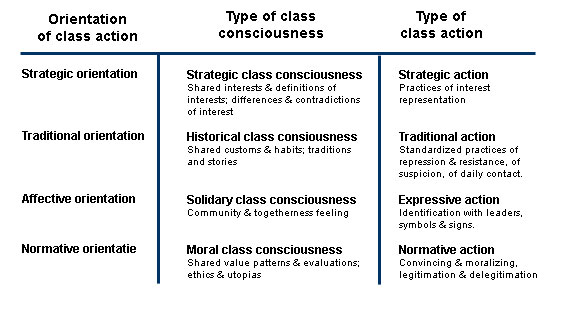

Figure 11 Orientations of social action - types of class consciousness and of class action

The proposition is that affectional, traditional, normative and strategic orientations and motivations are all relevant for an analysis of class consciousness. Class consciousness must not be reduced to one of these aspects. In search for a comprehensive, differentiated and empirically useful concept of class consciousness I discuss the contributions of Lukács, Thompson and Wright. I conclude this chapter with some remarks about the degrees of class awareness and types of class consciousness.

XIV. Class Interests and Class Action

The strategic dimension of class specific orientations and motivations will be separately dealt with in this chapter. First, I delineate the concepts of ‘interest’ and ‘class interest’. One of the main targets will be to avoid the utilitarian bias (i.e. the reduction of interest to ‘material’ or ‘monetary’ interests). This bias has plagued both Marxist and sociological analysis for such a long time. One of the main and long-standing questions was whether it is possible to speak about ‘objective class interest’ in a rational and non-paternalistic manner (the answer will be affirmative). A typology of class interests will be constructed and illustrated.

XV. Social Classes and Political Class Action

This chapter deals with the relationship between social classes and political class action. I specify the conditions under which political class action and social class movements can develop. The central thesis is that political class action and social class movements may (but not necessarily do) emerge when the members of a social class are able to articulate their common interests and aspirations, and to organize and mobilize their fellow members. I argue that classes don’t act: social classes as such are no big sized subjects with a will of their own and with a capacity for political action. I make some short remarks about the processes of articulation, organization and mobilization, the external conditions of political class action, strategic interactions between class-related political actors and the dynamics of class conflict. I expand on the role of utopian ideas and attitudes in class movements. With this chapter we’ve made the last step on the long way of unraveling the levels of structuration of class action. The most important concepts which were developed during this journey are summarized in a synthetic figure.

XVI. Reproduction and Transformation of Class Structures

The central thesis of this chapter is that class structures are constituted by social action, but also reproduced and transformed by social action. I summarize six mechanisms of action coordination that contribute to the social and temporal stabilization and/or guarantee of class structures: customs and morals; solidarity; interests; conventions, law and violence; and legitimacy. I demonstrate that all these reproductive mechanism also can lead, under certain conditions, to the destabilization and/or transformation of class structures.

Part 4 Transformational Class Analysis in Progress

In the fourth and last part of the book I discuss the transformational class analysis in development. Although this is a rather long book, the transformational class analysis is still an unfinished project.

XVII. An Unfinished Project

The last chapter deals with some problems which seem to be decisive for the future of this project. We’ve seen that the cornerstone of the heuristic model is the analysis of the levels of structuration and integration of class action. The problem is not only how to differentiate these levels, but of course also how their connections and intersections can be analyzed.

In the analysis of the levels of structuration I have assumed that the system structure (i.e. the structure of exploitative labour relations) structures both the positional structure (i.e. the structure of class positions) and the group structure (i.e. the social class structure).

I also assumed that the objective class position not only structures social classes, habitus and lifestyles, and the types and degrees of class consciousness, but also the conditions of class actions and the forms of class action.

The levels of structuration of class action that were described in the previous chapters are summarized in a little bit more complex figure. To keep the figure surveyable the graphic indications of all possible retroactive effects and interactions have been omitted. For the specification of the modes of structuraten it is therefore still a very rude model, which contains only some (mostly simple) causal relations between a limited number of basic concepts.

Figure 4 Levels of Structuration of Class Action

A reflection on the modes of structuration (i.e. ways to think about complex structural causality) demonstrates that we still operate with rather primitive structuration modes and that much more work has to be done.

A reflection on the relations between class theory and empirical/historical research shows how difficult it can be to navigate between the Scylla of (structural) theoreticism and the Charybdis of (sociological or historical) empiricism.

A final reflection on the problematic relation between class analysis and political strategy shows that it ain’t so easy to avoid instrumental and scientistic approaches. But we do gain some idea of the conditions and possibilities of a self reflexive class analysis.

Preface

I. Why class analysis?

In this study a new type class theory is presented. For sensible people such a statement calls for a healthy dose of suspicion and distrust. Social scientists who are still dealing with classes are soon under suspicion that they try to pull old cows from ditches which were filled long ago. In the current ‘post-socialist era’ it is more unusual than ever to write treatises about exploitation and class relations. since the collapse of the systems that advertised themselves as ‘real socialism’ the dream of a society without classes and exploitation seems to be shattered. Whoever is nevertheless concerned with the class theme or even writes a book about it, must be an inveterate nag or a dogmatist.

Moreover, in social science circles it is common to treat any claim on the ‘newness’ of a theory with great reluctance. I will not in advance hedge myself against such resistance and blame. I only hope that the reader will be able to put his or her ‘a priori resistances’ into perspective and is capable to judge for themselves on the (sometimes very difficult) problems which are dealt with in this study.

1.1 Reasons for a quest

The transformational class analysis that is presented here is the result of a long quest for the assumptions, basic concepts, methodology and internal structure of several class theories and the result of a very large amount of sociological, anthropological and historical studies of class relations.

There are several reasons to undertake such a quest:

- There have been some important shifts in the class structures of contemporary capitalist societies. The diagnoses that have been given of these changes in the social class structure are very diverse and incompatible. Yet there are some elements which no serious observer can ignore:

- the strong expansion of the modern wage-dependant middle class, and especially of the public employees;

- the contraction of the traditional middle class, especially of the small producers who work with their own means of production;

- the changes in the composition of the working class, especially of the category of industrial manual workers, and

- the emergence of new class categories such as professionals, experts and managers who can not be simply classified as part of the working or capitalist class.

-

However you want to analyses these changes and whatever names you want to use for these classes and categories, one thing is clear: all these changes entail new conditions and new forms of social and political class action.

The changes that are taking place in the class structures have confronted the socio-political movements and their organizations with new problems. Emancipatory movements, which in one way or another pursuit drastic reduction or even elimination of exploitation relations are repeatedly forced to reconsider their programs and strategies for action.

The explanatory models and methods that are used to get grip on the changing socio-economic and politico-cultural class relations, should be re-considered and tested again and again. This regularly faces problems for which the ‘old’, familiar concepts repertoire can provide no good answers. It makes no sense to keep silent about these issues or to push them aside — once they are declared taboo, one jumps from the scientific logic into ‘the logic of the sentiment’ (Theun de Vries), i.e. into socialist mysticism.

- Since the end of the sixties of the last century, the rise of the democratic student movement, the new forms of industrial action and the second wave of feminism led to a revival of the class debate. Sacrosanct declared ‘classic’ theoretical positions were subjected to a critical reassessment and there were heated debates on new theoretical approaches and research strategies.

It soon became clear that there are very different views about substantive and methodological issues — also and especially within the Marxist tradition of research— This is not a problem as long as the defenders of rival approaches resist the tendency to dig themselves so deeply into the ‘own positions’, that they will not be able to look over the edge of their own theoretical trenches. The potential benefits of intellectual rivalry could thus indeed be lost.

The fortifications that were constructed during the ‘cold’ war of attrition have been affected by cement rot and must be demolished to the ground. Anybody who wants to contribute to this should first concentrate mainly on a theoretically oriented structuring of the problems that are at issue in the analysis of class relations. Without such a problem structuring it is impossible to establish a minimal consensus — not even on the most basic questions on which any rational discussion should be based: on on what do we disagree, which arguments opposite each other, which basic concepts are controversial? Despite all progress is the lack of a sound problem structuring. This is still one of most notable weaknesses of the analytic class debate.

- According to many authors the attempts to reconstruct a class theory are still at the beginning.[ 1] After all the energy that is spend in thinking and talking about class theories, this seems excessive. But it cannot be coincidence that there are so few accurate and comprehensive empirical analysis of the current class formations. There is no class theory whose concepts are so systematically and methodically elaborated that it can be operationalized for and fruitful applied in empirical historical research.

1.2 Where does the shoe pinch?

In anticipation of what in this study will be discussed extensively, I will indicate where the class-analytical shoe pinches.

- Beyond structuralism and actionism

We have to develop a frame of reference that allows us to break through the misleading dichotomy between ‘structuralist’ and ‘actionist’ class theories.- Structuralist approaches focus exclusively on the analysis of the basic structures of class relations and are not able —unlike associative— to establish a systematic connection with political class act of social actors. They analyze ‘structures without actors’.

- Actionist approaches on the other hand focus entirely on the political action of class actors and their organizations, but are not able to analyse the social structuration of this class action. They analyze ‘unstructured actors’.

-

The transformational class analysis starts from a position beyond the old controversy between structure and action focused approaches: class actions are structured by class relations and class structures are generated, reproduced and transformed by class action. The object of knowledge of the transformational approach is not ‘class structure’ nor ‘class action’, but class-specific action structuration.

- Levels of action structuration

We have to develop an heuristic model that focuses on the multi-structured nature of class action. I will argue that class action is primarily structured by inequalities and differences of objective class positions and social classes, by differences of class-specific habitus and lifestyles, and by the different types and degrees of class consciousness. It is also affected by a series of specific conditions of political class action. Any non-reductionist theory class should include these five levels of action structuration and analytically distinguish them clearly. - Leves of action integration

We have to develop a heuristic model in which a clear distinction is made between the different levels at which class actions are integrated or aggregated. The transformational class analysis assumes that the structuring of class actions can be analyzed not only the societal level of action integration, but also at the organizational and interactional level of action integration.

With such a theory of structuration of class action it is possible to escape the traditional dichotomies of objectivism versus subjectivism, economism versus politicism, collectivist sociologism versus individualistic psychologism, determinism versus voluntarism.

On the one hand my approach is critical vis-a-vis common reductions the structuration of action to lifestyles, value systems, traditions and affective internalizations (culturalist, normativist and psychologist approaches).

On the other hand this approach remains at critical distance from approaches that reduce the structuration of action to material resources and rewards (vulgar materialistic, economistic or objectivist reductions).

1.3 What a class theory should deliver

Any general and non-reductionist theory of classes should involve all levels of structuration of action and make clear not only how these various levels should be analytically distinguished, but also how they are intertwined and influence each other in empirical practice.

Unfortunately there are no class theories with such a range and degree of differentiation. Most theories focus on one level of action structuration letting all the others underexposed.

- ‘Objective’ or ‘structural’ class theories ignore the importance of inequalities in habitus and lifestyles. This was delegated to social psychologists and cultural anthropologists, who in turn have no or only marginal attention for the structuring effect of positions in exploitation and class relations.

- In analyzes of ‘status-based communities’ and ‘social classes’ the centre of gravity are the very differences in habitus and lifestyle. These ‘social’ classes are contrasted with so-called ‘economic’ and ‘political’ classes, which are the focal point of analysis in the Marxist and elite theory tradition, but also in analyzes of the ‘market class positions’ in the Weberian tradition.[ 3]

- In some class theories the meaning of the conditions of political class action is completely ignored and the whole problem is delegated to separate theories of collective action. Or it is simply assumed that class structured inequality as such are always relevant for and have pertinent effects on consciousness and action.

A non-reductionist class theory should also include all levels of societal, organizational and interactional action integration and distinguish them clearly from each other within a heuristic model. Also on this point there are no class theories available with such a range and degree of differentiation.

- Societal class theories —both in Marxist and Weberian tradition— focus on only one level of action integration and leave the other levels underexposed. In societal class theories the importance of organizational and interactional class determinant is usually completely ignored or they are just thematized as ‘effects’ of societal provisions (i.e. without its own significance for the structuring of classes). The whole problem is delegated to separated organization and interaction theories.

- Organizational class theories —in the power and conflict sociological tradition— put a very strong emphasis on the direct power and authority relationships between members and units of the organization, and there is little or no attention to the underlying societal structure of class relations.

- In interactional class theories the exploratory eye is only or mainly focused on the structures and processes in networks of direct personal relationships. The societal and organizational structuration of these networks fall largely outside the scope of these theories or at best regarded as a ‘background’, as a décor or context in which individuals act and interact.

1.4 What is transformational?

In order to delineate my approach from rival approaches I deliberately chose the term transformational class analysis. This term reflects that I analyse class relationships as dynamic relationships which are constantly generated and transformed by human activities.

The transformational model of action structuration ties especially with the contributions of Roy Bhaskar, Pierre Bourdieu, Anthony Giddens and Erik Olin Wright. Although their theory programs diverge in many ways, I will use them as an important fulcrums for my project.

It is inevitable that the choice of the adjective also call forth associations with the transformational grammar of Noam Chomsky. He took language as a set of grammatical sentences. The purpose of his generative or transformational grammar was to be able to generate all the grammatical sentences of a language (and only those sentences). With his transformational grammar, he tried to grasp language generation as a dynamic process: it is a collection of rules by which each time new sentences can be generated that belong to the corpus of that language.

The family resemblance with Chomsky’s transformational grammar is that a transformational class analysis focuses on theory construction as a dynamic process. A transformational class analysis is essentially nothing more than a collection of theoretical statements (related concepts, hypotheses and methodologies) that allows to generate new statements (and above all: ask questions!) which belong to the corpus of this theory.

II. Reconstruction and construction of a class of theory

This study contributes to the development of a social scientific class theory in which the limitations mentioned above are broken up. The elements which are brought forward for this are the result of two adventures.

- The first adventures was an investigation into the assumptions, basic concepts, methodology and internal structure of class theories that were formulated in the Marxist research tradition. I searched for the analytical power and problemematic spots —lacunae, ambiguities and contradictions— within this theoretical tradition.

The relatively large variety of theoretical approaches within the Marxist research tradition made it necessary to draw comparisons, carefully weigh pros and cons of rival approaches, and to make substantiated choices.

To clarify such a —highly complex— assessment, I pay much attention to the analytical structure of the entire problem area. A differentiated problem structuring not only makes it easier to weigh the strength and weaknesses of various approaches, but can also reveal the challenges and opportunities of a ‘theoretical integration’.

- The explanatory power and relevance of the class of theories in the Marxist research tradition have always been controversial. There is no lack of criticisms on Marx’s class theory or on Marxist class theories. All these substantive, methodological and socio-historical criticisms are discussed in detail in: Benschop [1990].

And there is also no lack of attempts to formulate alternative class theories. Usually this was done in affiliation with the contributions of Max Weber. But there are also more original attempts to develop class theories with higher explanatory power and relevance, for instance in the tradition of conflict and power theories.

In other publications [Benschop 1987a, 1987b] I extensively analyzed the significance of Weber’s contribution to the theory of social inequality and classes. The following series of questions is crucial.- Has Max Weber formulated a general theory of social inequality in which class relations are thematized? Does his treatise on Class, Status and Party assume or imply a general theory of social inequality? Can Weber be regarded as the founder of a multi- or at least three-dimensional approach to social inequality?

- Did Weber develop a general or specific class theory ? To what extend may Weber’s approach or subsequent neo-Weberian contributions be seen as an alternative to Marx’s theory of class?

The results of this critical reconstruction of Weber’ theory of inequality and class are incorporated in various places in this study.

-

The second adventure was to involve both the critique of ‘the’ Marxist class theory as alternative class theories in the exposition of the transformational approach. In this study all these theories and critiques are discussed in various stages of the development of the transformational class analysis.

How much can a class theory still contribute to understand the existing social structures and dynamic processes? How much can a class theory still contribute to grasp collective political action and modern social movements? The answers to these questions are highly dependent on the type of class theory that one uses — they therefore vary with the specific approaches that are circulating of ‘the problem of class ’.

The explanatory power of a class theory can ultimately only be demonstrated by empirical and historical research. Although a large number of empirical-sociological, historical and anthropological themes are discussed, this study is no record of empirical research. It is a report of an attempt to construct a transformational theory of classes that facilitates and guides empirical historical research.

Today class analysis should primarily be approached as a scientific and political problem.

2.1 Reconstruction

For the design of a transformational theory of classes we can choose different reference points. For anyone interested in the structure and evolution of class relations in capitalist societies the texts of Marx are a fundamental resource to start with.

For a reconstruction of class theory one has to gain insight into Marx’s class theory. Unfortunately this is not so simple because. Marx has not written a separate, let alone systematic treatment of the problem class. His class theory is interwoven with his whole work — and not always in a clear, stringent and unambiguous manner. In many texts of Marx the concepts of class, class relations and class struggle are playing a central role.

An exposition of Marx’s class theory thus includes a reconstruction of practically his entire oeuvre. A systematic review of the Marx’s contribution to class theory is tricky because all these texts have a different setting, thematic objective and theoretical status. The various texts of Marx are coloured by the problematics which he worked on and wrote about at that moment.

The interpretation and reconstruction of Marx’s contribution cannot be limited to the collection a number of striking phrases from his work. With each quote one should take into account the specific socio-historical and theoretical context of his statements, and the varying theoretical status and socio-historical scope of his concepts and statements. One should also take into account a rather difficult methodical-theoretical problem: Marx’s theses and hypotheses are formulated on different levels of abstraction and only valid for specific units of analysis.

If you don’t take all this into account, you’ll soon get the impression that the works of Marx (and Engels) contain merely contradictory, ambiguous phrases of which only ‘the true believers’ are able to bake theoretically bread. There have been various attempts to identify the inconsistencies and contradictions in Marx’s work by a compiler method. So far they have yielded little of substance. They are merely a useful preliminary work for a systematic reconstruction.

Fortunately there are a number of serious attempts to reconstruct Marx’s theory of class in a more systematic way. In the design of the transformational class theory I shall gratefully use them. However, this study is not a systematic reconstruction of Marxist class theory. For this I refer to my preliminary study: De klassentheorie van Marx.

2.2 Construction of a class theory

For the construction of a transformational class analysis I’ve chosen a different approach and a different reference point. The reference point of this project is the pro-theory of social inequality and collective action as elaborated by Bader/Benschop (Ongelijk-heden) and by Bader (Collectief handelen).

This pro-theoretical frame of reference provides a useful starting point for the construction of a transformational class theory. The pro-theory of social inequality and collective action does not impose a specific class theory. But it does offer a number of criteria to assess the complexity and scope of class theories, it puts theories under pressure to explicit implicit assumptions, to strengthen or overhaul rudimentary theoretical elements, to give explicit justifications of concepts and to limit or specify the validity claims of theories. In short, it provides clues for the construction of a ‘better’ class theory.

Theory class is part of a much broader conceptual framework. As part of a social theory it is a regional theory of class relations in social formations. Class theory is part of the political sociology of social inequality. The central thesis is : ‘Class’ is a crucial concept for the development of a systematic theory of social structure, especially of a more comprehensive theory of social inequality.

A substantiated and elaborated general theory of social inequalities does not exist. There are a number of partial theories, but these are so burdened by their general pretensions and substantial reductions that they can’t be used as a reference for class theory.[ 4] The most fruitful point of reference is a pro-theoretical framework in which basic concepts are substantiated and where the whole problem complex of social inequalities has been disaggregated in a profound way.

The object of the class theory is the structure and dynamics of class inequalities and conflicts. As a ‘sociological’ theory it depends and relies on many other regional or disciplinary theories. Class Theory must not be reduced to a narrowly regional —‘economic’ or ‘political’— theory. A theory of structure and dynamics of class relations in capitalist societies depends on the results of various social sciences, including social and economic history and anthropology.

My transformational class model is based on a critical assessment of some older and recent debates and relevant research from several social science disciplines. Former theoretical questions are redefined, new themes are added to empirical historical research agendas, and methods of empirical class analysis are refined.

III. Werkwijze: procedure van theorievorming

Theoretical texts are not so much a confrontation of ‘word’ and ‘reality’, but rather have the character of a conversation in the midst of other conversations. To some extent this study is also a compilation of various conversations and confrontations with other theoretical and empirical-historical texts.

This conversation basically goes along two lines: deconstruction and reconstruction. The design of a systematic theory is rather ‘complicated’ because there’s so little to hold on when we try to figure out how we should proceed. It implies a whole series analytic and synthetic operations that are not always clearly distinguished. In the process of theory development we can generally distinguish three analytical operations: deconstruction, reconstruction and construction.

3.1 Deconstruction: explication and interpretation

Deconstruction involves two analytical operations: explication and interpretation. First we have to explicit the problem definitions and analytical strategies relevant class theorists. Explication means identifying and clarifying the central problem definitions and basic concepts, without counting the full theory or approach into the consideration process. [ 5] The objective is to improve the problem definition, without abandoning the basis of the original problematic.

Explication particularly happens by situating texts in contexts. I will make a distinction between three contextual regimes.

- theory-historical context: explication of the meaning of texts in the history of a particular theory or theoretical tradition;

- theory-systematical context: explication of the position of statements —hypotheses, propositions, concepts— in the systematics or structure of a theory, and

- socio-historical context: explication of the connection of texts with the actual, ‘external’ history of society.

After these explicatory operations we have to interpret theoretical texts. Interpretation is done by demonstrating the relationship between problem definitions and analytical effects (problem solving). This allows us to detect conceptual ambiguities, inconsistencies and substantive theoretical shifts, and to identify the main and subsidiary tendencies in the structure of a theoretical approach.

The ‘scandal of deconstruction’ (Norris) is indeed the habit of exposing disjoint relationships between the logic of a theoretical explanation and the language in which it is formulated, between the order of the immanent coherence of the concepts and the order of significance, i.e. the relationships between the signs of meaning (signifier), including the vagueness, ambiguities and metaphors of the written language.

3.2 Reconstruction: reassemblage

Explication and interpretation result in a rating of theoretical consistency, scope and explanatory power of a specific approach. In combination with a comparison with other theoretical approaches we are then able to separate concepts with a ‘past actuality’ (bygone concepts) from concepts with an ‘actual past’ (actual concepts).

These latter elements are the building blocks of a systematic reconstruction, i.e. the reassembly of a theoretical construct using the insights acquired by explanation and interpretation. By filling the lacunae in a theoretical program and by detailing its global concepts (disaggregation) we can finally try to improve class theory. In this process we often ‘borrow’ elements from theories which have been developed in divergent research traditions.

3.3 Construction

The construction of a new class theory is a distinctive and complex affair. The concepts from which this theory is built should be defined as sharp as possible (demarcation of concepts); the levels of abstraction on which concepts and their interrelationships are formulated should clearly be distinguished; the interdependencies between the structuration levels of class action should be specified; causal explanation models must be developed; rules should be established for operationalization of concepts; and methods should be proposed for the empirical study of class relations.

The core of the construction of any scientific theory it is dual process of specification of concepts and using these concepts in the construction of a theory. Both in the revision of existing concepts as in the introduction of new concepts the assumptions underlying them must be exposed. Moreover, the interrelationships between these concepts must be made explicit so they can merge into one theory.

New concepts do not arise in a theoretical vacuum , and there is no theoretical zero point. Concept formation is always also —and perhaps primarily— a process of concept transformation: raw materials of existing concepts are processed in the construction of a new concept.

For the (trans)formation of concepts we can use different practical strategies [Wright 1985:292 ff].

- We can decompose an existing concept by pulling new demarcation lines. This happens especially when in an existing concept heterogeneous elements are brought together under one hat (‘breaking down concepts’).

- We can specify an existing concept by redefining existing demarcation lines. When the boundaries of a concept defined by redundant, insufficient or inaccurate criteria than those criteria should be modified.

- We can broaden an existing concept by reaggregating categories under more general criteria. In this case existing concepts are subsumed under a more comprehensive concept, i.e. a concept that identifies a fundamental border criterion for the concepts which it aggregates.

- Finally we can decode the conceptual dimensions of a descriptive taxonomy. Descriptive taxonomies are transformed into conceptual typologies. A taxonomy is a set of categories which are identified on the basis of immediately evident empirical criteria. [ 6] A typology is a theoretically constructed series of concepts that are differentiated on the basis of theoretically specified dimensions. In a decoding strategy of conceptual (trans)formation the implicit, non-theorized logic of the applied taxonomy is made explicit.

In the design of the transformational theory of classes the four analytical operations (explication, interpretation, reconstruction, construction) nor the four practical strategies of conceptual (trans)formation (decomposition, specification, broadening, decoding) are not dealt with in a separate-chronologically order. All these operations and strategies are interwoven and therefore often difficult to recognize — they are passing simultaneously (‘arm in arm’) in review.

IV. Limitations of the study

The design of the transformational theory of classes is ambitious and massive, but not without some limitations.

- This study does not provide detailed reconstruction of a specific class theory or a particular research tradition. The history of the class concept is cursorily handled. I will not give a comprehensive theory-historical or chronological overview of various denominations, theoretical positions or authors. The different currents and authors are always treated problem-oriented. They are discussed in the order of the points where they are important for the construction of the transformational explanatory model.

In this way a picture will be outlined of the pros and cons of the various class analytical research traditions. All relevant theories and research approaches are assessed both on their explanatory power and their internal obstacles, aporias, think blockages and lacunae. Incidentally, the transformational class model does provide an analytical and methodical framework that enable critical reconstructions of alternative class theories.

- The transformational model is a starting point for a systematic class theory and it therefore has further pretensions than a pro-theory. Concepts are defined and related to each other, distinct levels of analysis are compared with each other and regularly (tentative) causal explanations are given. The end result is not a ‘system of class theory’. The individual chapters are best read as ‘systematic essays in class theory’.

- This study is not an empirical-sociological analysis of class relations in modern capitalism. It refers extensively to empirical-sociological, antropological, historical and political-economic studies. They are used to analyse the emergence and transformations of class systems, to draw attention to theoretical gaps, and to illustrate current developments in class relationships. The emphasis is on formulating research questions and specification of research strategies. Problems in operationalising concepts are discussed when necessary.

- No normative theory of exploitation and class relations is presented in this studie. I have confined myself to the profiling my own normative assumptions and political references (‘knowledge interest’) that are associated with this kind of research. And I will give a few critical comments on the normative presuppositions or implications of competing class approaches.

- What is the social relevance of the whole enterprise? Can the transformational class analysis contribute to emancipatory movements?

The intention is clear. The transformational class approach can increase the awareness and cognitive autonomy of collective actors who challenge exploitation and class relations (and therefore facilitates their action autonomy).

The pretension however is very modest. The transformational class analysis provides good foundations for the design or assessment of practical action strategies of emancipatory movements and their conflict organizations, but it does not provide ready-made or ‘realistic’ political strategies.

V. Composition of the study

5.1 Preliminary skirmishes

The study is divided into four parts. The first part contains a number of Preliminary skirmishes.

Chapter I outlines class analysis as a scientific problem. It discusses how class relations appear in everyday consciousness and in the attitudes of people. After a first attempt to demarcate a social scientific concept of class, the antecedents of the concept of class are analysed. This results in a basic typology of class definitions. After discussing some theoretical reference points which are relevant for the study of class relations, I give a provisional definition of the knowledge object of class theory and delimitate the structural and socio-historical scope of class analysis.

In Chapter II class analysis is treated as a political problem. First I make my own political and normative assumptions explicit. Then I give a critical discussion of the political claims that class analysis has usually been saddled with. I discuss three closely entangled political problems: (i) the utopian perspective of a classless society, (ii) the social actors or carriers of such an utopian project, and (iii) the connection between class theory and political action strategies aimed at breaking the existing exploitation and class relations. One thing seems clear: the analysis of social classes and their mutual struggle itself is at stake in political struggle.

In Chapter III an analytical structure is applied that encompasses all the problems that have to be processed in a theory of classes. It aims at two objectives. First, I design an fine analytical network which helps us to develop class analytical research programs. Secondly, this problem structuring is used to give a systematic overview of the existing range of class theories. It clarifies which choices are made by researchers and which other choices could have been made. I also explain which choices I made and why, and which analytical trajectories and methodological routes are rejected

Most researchers agree that class relations can be understood as a specific structural form of social inequality. Therefore Chapter IV starts with a compact exposition of the concept and forms of social inequality. The usual basic distinctions are examined: natural and social inequality, social differentiation and social inequality, positional and allocative inequality, incidental and structural inequality. From this perspective six general propositions are formulated that constitute the ‘hard core’ of a class analytical research program. Taken together these six propositions are the platform on which the rest of the book builds. These basic propositions will be specified, developed and concretized in the following chapters. Each chapter begins with an additional proposition which is first demarcated from other approaches and then substantiated and elaborated.

5.2 Structuration of objective class positions

The second part focuses on the question how the structuring of objective class positions can be analyzed.

Chapter V plays a key role because it outlines the principles of the transformational class approach. As already noted, the centre of this approach is the analysis of the structuration of class action. For the analysis of this structuration process I will introduce five types of distinction.

- A distinction between the levels of abstractionat which class relations can be analyzed.

- 20160426063109/http://sociosite.net/class/summary.php#XVA distinction between the units of analysisof empirical research.

- A distinction between five levels of structurationof class action, and between the corresponding processes that constitute these structuration levels;

- A distinction between three levels on which class action is integrated: levels of action integration

- A distinction between the mechanisms that maintain and reproduce class structures and mechanisms that destabilize and transform class structures.

These substantial-methodological distinctions are moulding the scaffolds for the construction of the transformational class theory. The order of the remaining chapters parallels the levels of action structuration that are distinguished. Those who already wants to get an idea of this construction I refer to the summary review in Figure 15 [see part XV of English summary]